Towards the prevention of rebound effects

In 2022, Daniela Pigosso received the prestigious ERC Consolidator Grant for her research project Reboundless. The Associate Professor belongs to the Section of Design for Sustainability at DTU Construct and is associated with DTU’s Centre for Absolute Sustainability, which was also launched in 2022. It aims to establish methods and technology that can help humans live within Earth’s boundaries without adversely affecting its ecosystems.

The Reboundless project deals with how to design technologies, products, services, and systems that are resilient to rebound effects, so that we achieve the intended sustainability gains. Mobility is just one of the focus areas. Several other rebound effects can be identified across other societal needs, such as housing, nutrition, and consumables.

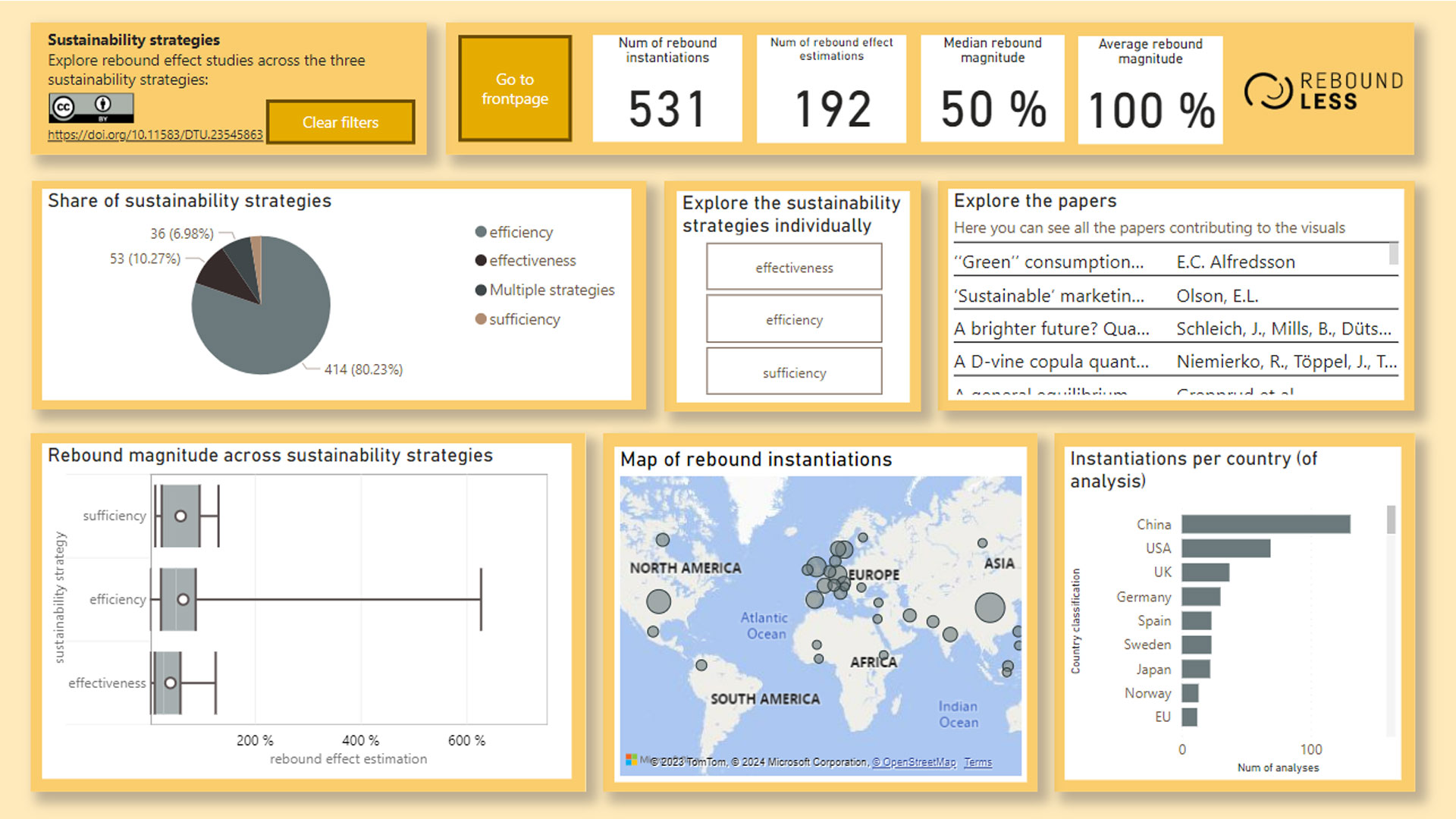

The project team has already introduced the first tool—a dashboard that industry, government, and academia can use for free. It pulls together information gleaned from a systematic literature review of 1413 papers that deal with rebound effects. Data from papers that met the team’s criteria for inclusion have been classified according to several categories and put into an online dashboard, which gives an overview of the kinds of rebound effects registered and their magnitude.

Organizations planning to implement a sustainability solution can use the dashboard to learn about any known rebound effects in a given area as well as their size.

“The dashboard indicates how important it is to work on mitigating possible rebound effects. If they are less than five per cent, then we can probably live with that. But if it is 7000 per cent as we saw in the case of environmental rebound effects connected with the introduction of more efficient diesel cars then you can see this is really something you need to investigate,” Daniela Pigosso explains.

Easier access to data

The Reboundless team will keep updating the dashboard as new data is published. It will help ensure that researchers don’t have to start from scratch when embarking on a research project.

“Over the past 30 years or so loads of research has been published on rebound effects. But that knowledge wasn’t consolidated anywhere. Our main goal is to move people away from reinventing the wheel by doing the same studies over and over—and to help identify data gaps so that we as a scientific community can work to fill those gaps instead,” Daniela Pigosso says.

One such gap identified by the team is that most studies only evaluate rebound effects at a given point in time, either in the past or in the future. While this provides valuable information, having knowledge of rebound effects over time would make the insights so much more useful. If you don’t understand the evolution of rebound effects, you might see different rebound magnitudes depending on when they are measured. You may even completely fail to anticipate certain rebound effects, Daniela Pigosso explains.

“It’s extremely important to have a dynamic estimation of rebound effects so we can see trends over time and compare the say 10 per cent rebound effect we are seeing today with how things were last year or are expected to be in ten years,” she adds.

Better design is key

Until now, a prime research focus up has been on policy as a way to reduce rebound effects. However, policy is only part of the puzzle – and there are plenty of examples of well-intentioned policies that have led to rebound effects.

In the city of São Paulo in Brazil, for example, policymakers attempted to curb congestion and pollution on the populous city’s roads. They banned cars with license plates ending with certain numbers from driving on certain days. However, rather than leading to a reduction in traffic, the policy led people to buy another car with a license plate with a different number, which made traffic significantly worse than before.

In the Reboundless project, the focus is on preventing rebound effects already in the early phases of the design of new products, technologies, and systems. They do this across four societal needs: housing, nutrition, consumables, and mobility which together, contribute to ¾ of the total global carbon emissions.

“I’m convinced that design is a really strong leverage point for preventing the occurrence of rebound effects. If we design our solutions in a way which prevents rebound effects, we can really make a difference and achieve the necessary sustainability gains. And we can do so here and now, before any future consumption moderation policies are implemented.”

In addition to explaining when, how and why rebound effects happen, Reboundless will also enable the dynamic simulation of potential rebound effects over time, informing decision-making in the early stages of design towards the design of reboundless solutions.

“Imagine how beautiful it would be if instead of having a rebound effect, we could design solutions that trigger secondary benefits. This would enable us to achieve even more good than expected. Turning rebound effects into secondary benefits would be an amazing outcome of Reboundless!”